Through the Pain

Students discuss their chronic conditions and what the University of Minnesota is—or isn’t—doing to help

Most of the people you know start their day with an unlimited number of spoons. But you have 15.

Each spoon you hold represents the amount of personal energy it takes to complete a task. Getting out of bed costs you one spoon, so now you have 14. As you prepare for the day, maybe you need to choose between a morning dog walk or a long commute. Either way, you’re losing two spoons. Whichever you choose, and whatever task you complete during the day, costs you. Your goal? Make sure that your day ends before you run out of silverware.

This concept is called The Spoon Theory. It was created in a diner, over french fries and gravy, by writer and blogger Christine Miserandino. She was struggling to find a way to tell a friend what it’s like to have Lupus until it occurred to her that each spoon at their table could be used to represent the limited resources a person with chronic conditions needs to honor as they navigate their day-to-day. When a person only has so many “spoons” to allocate (and again, people without chronic conditions have many more spoons) they have to make choices that healthy people may not have to think about in the same way.

According to the U.S. National Center for Health Statistics, conditions are considered “chronic” if they last for more than three months and include diseases like diabetes, arthritis and cancer, as well as mental diagnosis like PTSD and ADHD. Whether the symptoms a person experiences manifest as pain, an incurable disease, or another form of disability, having a limited number of “spoons” can add challenges to everyday actions as well as life-altering endeavors—like attending college as an undergraduate.

When I walk into the Disabled Student Cultural Center (DSCC) in Coffman Memorial Union at the University of Minnesota, I’m first greeted by the soft ding of a bell. It is one of the ways in which the space is accessible, as it indicates to those with visual impairments that you have arrived.

Students sitting in a circle holding a board meeting raise their heads at the tone of the bell. Instead of irritation at the interruption, inquisitive smiles and a range of “hellos” act as a second greeting, followed by an offer to join them.

The front of the room is filled with tables with enough seats to host the occasional game night or coffee meet-up, just two of many events that the DSCC organizes to provide opportunities for students to discuss their experiences navigating campus with a disability. The back area is packed with couches available for quiet studying or casual conversation.

As a registered student organization, the DSCC is a self-proclaimed “safe space” for students of all backgrounds and abilities, with a mission to “foster the culture of students with disabilities and increase disability awareness on campus.” It’s one of the resources for students with chronic conditions or disabilities that the university has to offer, along with the Disability Resource Center (DRC.)

The DRC, which served nearly 3,800 students in 2018, provides logistic and academic support. The staff’s goal is to minimize or eliminate barriers students with medical conditions or disabilities on campus face. In most cases, a student who comes through their doors meets with one of 18 “access consultants” to talk about challenges that may come up in the classroom and beyond. Accommodation letters can be drafted for clients, according to Emily Ehlinger, a student access manager at the DRC. The letters, which can be given to professors and other faculty, provide accommodations such as attendance forgiveness, extended time on exams, note-taking assistance and modified assignment deadlines. Access consulates are also available to help with any difficulties that might arise between a student and instructor.

Ehlinger says that students with mental health-related disabilities account for the highest number of those registered with the DRC. ADHD and learning disabilities rank second and third, followed by chronic health conditions.

Anthony Lawlor, 29, is the vice president of board at the DSCC and has been on a journey toward a college degree for a decade. When talking about his years of college experience, he will tell you the sequence of events is a “confusing maze.” Celiac disease, diabetes, and being visually impaired have complicated Lawlor’s college career.

Lawlor started college at the University of Minnesota Duluth (UMD) at the age of 19. During that first year, he was forced to withdraw for health reasons. He returned later only to withdraw a second time, still having various health complications, chief among them stomach issues. “When I withdrew that time, I thought I was done with college for good,” Lawlor says.

Lawlor didn’t return to UMD. Instead, over the next few years, he tried jobs here and there that ended up exacerbating his health problems.

After a move to the Twin Cities and attending classes at Minneapolis Community and Technical College (MCTC), Lawlor decided to transfer to the University of Minnesota in the spring of 2018. He is currently studying in the intercollege degree program with a focus in applied business, leadership studies and communication studies.

“It takes time to find ways to deal with all your issues and what works best for you,” Lawlor says. “Going to MCTC wasn’t ideal, and then I found out what I didn’t like and what I really needed, and that’s how I ended up here.”

Being at a big campus has its positives and negatives, according to Lawlor. One point of contention Lawlor faced at the university was housing. He needed his own apartment, mainly for the ability to cook his own food, both because of his illnesses and the dining halls “inadequate options.”

“There is no way I can eat at a dining center here. Even though they say they have some things, they give you a frozen dinner every meal. Or you can eat cereal or PB and J or something like that,” Lawlor says. “A lot of people with dietary restrictions, they get sick like every other week because of that. It’s a big issue.”

Despite his difficulties with housing, Lawlor ended up getting the apartment he needed, and says that he is pleased with his experience at the U of M. “This is the best environment I’ve been in so far, and it’s taken trial and error to find it. I think it’s about being patient with yourself and giving yourself time to find out what works for you.”

Lawlor’s involvement in the DSCC has dramatically improved his college experience. The center provides him with a place to exchange stories with other students about how to work around barriers that arise due to chronic illnesses and disabilities. “If I hadn’t applied here, I would not be as connected,” he says. “I wouldn’t have a community on campus. I wouldn’t have met all the friends I have. It would not have been good.”

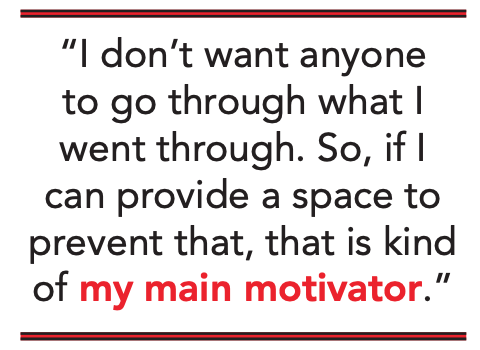

Lawlor says he works at the DSCC to help ensure that no student has to experience the feeling of isolation that can come with having a chronic illness like he did in his first year of college. “I don’t want anyone to go through what I went through,” he says. “So, if I can provide a space to prevent that, that is kind of my main motivator.”

Ellen Schmidt would have loved to know other people that were going through the same things she was as a student with a chronic illness. Schmidt is a former university student who was diagnosed with severe Crohn’s disease at age 11.

Although Schmidt never found her way to a student support group, she says a space to meet people with similar experiences would have been helpful. “Having a space to make friends with those people would be cool,” Schmidt says.

Crohn’s disease, a chronic inflammatory disease of the digestive tract, can be exacerbated by stress. The new environment and higher stress levels that come with college life changed the amount of time Schmidt had to rest to keep up with her health.

“The food was different, all sorts of things that are difficult for a person to manage. So that definitely changed things,” Schmidt says. “And just realizing that I needed to take time to rest was, I think, a thing that people who don’t have chronic illness didn’t have to figure out in the same way that I did.”

But Schmidt wouldn’t say she is balancing anything when it comes to her health and academics. “It is part of who you are, so you just have to deal with it,” Schmidt says. “I never really felt like I was balancing anything. I was just doing it.”

Before discovering she was eligible for support through the DRC her junior year, Schmidt knew she was going to lose attendance points in most of her classes. After using up all the “free” absences students are allowed in most classes, Schmidt would try using doctors notes to account for missing class. But that didn’t always work. “I had professors that wouldn’t take doctors notes,” she said. “They were like, ‘That’s too many of them.’” So, the professors would dock Schmidt’s grade, and she felt forced to stay silent.

With attendance being a huge negative strain on Schmidt’s class experience, getting her accommodation letter made her feel better about her classes and the view her teachers had of her. But the accommodations didn’t come without a catch.

The letters from the DRC to professors do not explicitly state the reason a student needs accommodation. Schmidt usually opted to tell her teachers about Crohn’s out of fear that the professor would assume her reasons were less than adequate.

“I am afraid of them actually discriminating against me,” Schmidt says. “I wouldn’t choose to tell my professor, whom I do not know at all, the personal details about my life if I didn’t feel it was necessary.”

Letters from the DRC alone are not always enough to ensure that students will actually receive accommodating conduct from faculty and professors.

“We see some instructors who are really familiar and really accommodating,” says the DRC’s Ehlinger. “We also experience instructors who are less familiar with the accommodations process and are really unsure about what is reasonable in their class.”

One way to strengthen faculty’s understanding of the needs of students with chronic conditions is to implement professional development resources to help teachers learn how to support these students, according to Carolyn Berger, assistant professor in the department of educational psychology.

Berger has done a great deal of work with students with chronic illness. Even though her research focuses on K-12 students, she says professional development resources for teachers are essential at all levels of education. According to Berger, it is important for professors to understand how chronic conditions can impact students, and to have access to resources that can help them with that task.

“A professor may say ‘Okay, now I know my student is diabetic. What does that mean? How can I best support them and provide them the best educational experience they need?” Berger says. Having a system in place for professors to access that kind of support would benefit both students and teachers.

Berger acknowledges that this may be difficult for a professor with 100 students in a class, but says, “It may be a lot of work, but I don’t think it would be unattainable.”

One answer to how to better prepare professors to accommodate students with chronic conditions comes from a newly formed branch of the DSCC, a disability advocacy group. According to Lawlor, one of the main goals of the brand-new group is to require faculty training in the form of informational videos to educate them about disability issues and better prepare them to help students with disabilities.

Even a fundamental understanding from professors is something that some students with chronic conditions find to be rare.

Schmidt says professors “are taught to just go by the letter, so they don’t have to learn any of that other stuff.” Professors not wanting or needing to learn more makes her feel like, at times, they are just taking a short-cut.

“I’ve never had a teacher that really understood it [Crohn’s], never. And I’ve had it since I was 11,” Schmidt says.

It is hard to imagine a topic that Juliana Q. would be uncomfortable or unwilling to talk about.

Juliana uses they/them pronouns and prefers to be identified by first name. “I am 23. I have memory problems. That’s one of my many disabilities,” they say with a grin.

A senior at the university, Juliana has not only become very passionate about mental health and disability, but also very comfortable talking about it. In fact, Juliana does it with a genuine sense of humor. When talking about life with multiple physical health diagnoses, as well as conditions like ADHD and PTSD, they have such a cheerful and matter-of-fact demeanor that even a sentence like, “Every year I seem to get less healthy, and I’m like… Why is my body breaking?” is accompanied by a smile and light-hearted shrug.

Juliana didn’t realize they had anything that would qualify them for accommodations, or as disabled, until sophomore year. That’s because being in college makes it easier to rationalize away the idea that you may need an accommodation, they say. During that first year, Juliana says thoughts like, “I made it this far. I have the ability to get into this level of privilege, this level of academia, of course I don’t need accommodations,” were typical.

Now, Juliana endearingly calls those thoughts “wholly nonsense.” Before getting accommodations, Juliana was sleeping 18 hours a day and missing classes. “I often times had to email teachers, like, begging for extensions.”

Juliana would pad emails with “large amounts of angsty back story” to try to get extensions for assignments. Juliana didn’t like bearing their personal stories to professors, but anything was better than the professor writing Juliana off as “that lazy student.”

But once Juliana had an accommodation letter, the days of asking for extensions through personal emails were replaced with more relief, and less absences. “As soon as I got attendance forgiveness, I stopped missing classes,” Juliana says. “As soon as I knew that I had a safety net, and I was allowed to miss class if I needed to, I stopped being as anxious to go. So that was kind of beautiful.”

Although student life after the accommodations has improved, there have been instances when professors failed to be truly accommodating, according to Juliana.

One time, a teacher said: “You know, you using these [accommodations] feels very unprofessional.” In Juliana’s special education major, students are actively graded on levels of professionalism. Therefore, the comment from the professor felt threatening to Juliana. “I never used accommodations in that class again,” they say. “I pushed myself way harder than I should have and I hurt my health for it.”

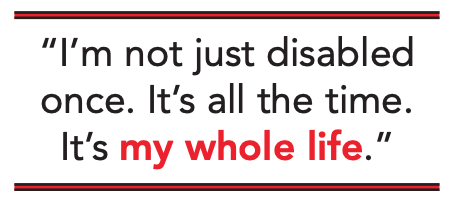

Juliana had another professor say that while using the accommodations once was acceptable, doing it again would be frowned upon. “I’m not just disabled once. It’s all the time,” Juliana says while recalling the incident. “It’s my whole life.”